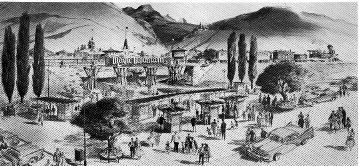

Above is the artists’ illustration of the entrance to Magic Mountain, and the entrance as it stands today. Natural scenery was paramount to the concept of Magic Mountain, which called for integrating itself into its natural setting at a mountain site, incorporating natural landforms and even creating new natural landforms like lakes to realize its vision. Ground was broken in 1957, and this entrance area was finished in 1959. Elements such as the railroad trestle, blockhouses and Victorian spires familiarly greet visitors still today. Magic Mountain’s theme: A re-creation of the Old West of the year 1858. That was the year of the first permanent settlement in Jefferson County: Arapahoe City, just east of Golden on Clear Creek, and only 3 years ahead of the settlement of Apex. The entire core Victorian village of Magic Mountain, named Centennial City, was built in 1958, to include various kinds of shops straight out of the Old West.

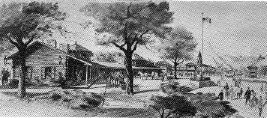

The first building constructed at Magic Mountain, completed in early 1958, stands to the south of the entrance today. This was the Cavalry Post, with its companion Stockade right next to it to the south. Constructed of native logs, the Cavalry Post served as the administration center for Magic Mountain. Nearby were constructed twin log Blockhouses, of the type once used on the frontier for shelter from raids. There was a prime reason the Cavalry concept was chosen for the first building and theme, which may be read later on in this exhibit.

A full-scale narrow-gauge train, the Magic Mountain Railroad, was constructed to encircle Magic Mountain, using the historic Denver & Rio Grande Locomotive #420. This had been manufactured by the Baldwin works in 1889 and had served a fruitful career across Colorado. An ornate High Victorian Gothic depot was built near the park’s entrance, far more impressive than any depot Jefferson County had yet seen. This depot was later converted into a restaurant when the park was converted to Heritage Square, and is now its events center. The historic locomotive resumed service at Heritage Square in 1971 as part of the High Country Railroad, and in 1975 it was replaced by an unusual engine, the Lima Shay 3118. This was a 10-ton shirt pocket 3 cylinder 2 truck Shay built in 1920, which departed from the company’s usual practice of using Stephenson valve motion, instead using walshert motion for the valves and a common steam chest for all cylinders. This was retired in 1998, and the rail line was reconstructed as a miniature gauge of 15 inches. Thus the railroad was reborn as the Heritage Square Narrow Gauge Railroad (really narrow!), led by Denver & Rio Golden locomotive #463, a miniature steam engine of K-27 2-8-2 scale built by the Ulrich foundry in Strasburg, Colorado.

Above is the artist’s view and the reality looking northwest across the entry of Centennial City, towards the present-day Heritage Square Music Hall building. Centennial City’s buildings were actually singular, 1-story steel-framed structures built with a number of different frame storefront facades on to make each building appear like city blocks of individual buildings. Rubottom and Kelsey used detailed research into Colorado history to create buildings of historic styles from the region and Golden itself, including Gothic Revival, Second Empire, Greek Revival, Pueblo Revival, and more. They used these styles with convenient 1950s-era storefront display styling. Then these art directors employed a time-honored Hollywood design technique on their buildings, the art of forced perspective, making Centennial City appear taller than it actually was by miniaturizing building elements as they reached upward. Rubottom had successfully used this technique before while helping design Main Street USA at Disneyland. Moreover, a horizontal form of forced perspective was used, narrowing each storefront in accordion-like fashion to make each block appear longer than it actually was. The intended result of the use of forced perspective was to give Centennial City a believable, but friendlier, scale and feeling than historic downtowns normally have. The art directors also utilized creative distortions and embellishments on building details to soften their appearance and give them an almost whimsical, gingerbread feeling.

The southern building at the village’s entrance was the Magic Mountain Play House. After the advent of Heritage Square in 1971 this original theater served as the comedic institution that is now the Music Hall. This institution originally began as a group of comedy melodramatic players in Estes Park in the early 1970s led by G. William Oakley. In 1972 the players moved to the playhouse and became the Heritage Square Players (the old stage may still be seen inside the alcove at the west wall of the easternmost store room). In 1973 the Players moved across the street and retrofitted the storefront there into the Heritage Square Opera House. They filled out a full second floor to the structure, which previously had been like all other Centennial City buildings in that it had a cleverly deceptive 10-foot false upper floor (even false stories made these buildings truer imitations of more old west buildings than historians might care to admit!). When Oakley left and the Opera House shut down, T.J. Mullin and the players reopened the venue in 1988 by creating the Heritage Square Music Hall. Today the Music Hall remains as one of Heritage Square’s premier attractions.